This entry is LONG! It covers the Kaliningrad leg of my tour, from June 12 - 18. Those who want to know every detail of my life will find it riveting. The rest of you can scroll through for whatever interests you — for example, pictures of people and places and birds!

June 12, 2019

From Winchester I traveled to London-Heathrow Airport and from there caught a plane to Kaliningrad, with a brief layover in Warsaw.

On my first visit to Kaliningrad (in December 2017), I traveled to and from Gdańsk by bus and stayed only one night. It was a brief but powerful whirlwind that left my heart aching for more.

Some background on my “Russian connection,” because people often ask. I became interested in all things Russian when I was a kid, after reading Gloria Whelan’s Angel on the Square and Carolyn Meyer’s Anastasia: The Last Grand Duchess. This was before the days of Duolingo, otherwise I surely would have started learning the language immediately.

Years later, in 2005 (my first year at the University of Oregon), I heard Regina Spektor’s “Après Moi,” which includes lines in Russian from the poem “February” by Boris Pasternak. The sound of the words mesmerized me. Soon after this, I learned that the U of O had a Russian program. Before committing to the language, I decided to take a Russian literature class. We read a few short stories by Tolstoy, Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, selections from Shalamov’s Kolyma Tales, Nabokov’s Speak, Memory, Bulgakov’s Master & Margarita, and Lyudmila Ulitskaya’s Sonechka. All of it blew me away. I started listening to a Russian language learning podcast, and over the summer I read as much Russian literature as I could. In the fall, I enrolled in my first Russian course, and finally, in 2018, I graduated with my B.A. in Russian.

Okay, back to the current story.

A few months ago, Vlad (who organized my first show in Kaliningrad) and I started Skyping so we could work on our English and Russian speaking skills, respectively. Vlad radiates kindness and warmth like few people I have met. His general way of being in the world reminds me of the lines from Regina Spektor’s “The Light,” addressing her son and her husband: “You and your daddy, you look like poets / Your eyes are open wide while you are in a dream.” The first time we Skyped, he smiled and said, “I’m so happy to see you. You look good.” Offhand, I can’t recall many (or maybe any) times a straight man has said something like that to me. That’s Vlad.

Airport flowers.

In Kaliningrad-Khrabovo Airport, paper-wrapped bouquets of flowers rotate in vending machines near an island of shops dripping with amber souvenirs.

The previous night, I had played a Sofar show in Chesterblade, a village near Frome, and it was so cold enough inside the heritage farm house you could see your breath. Kaliningrad, on the contrary, was blazing hot from the moment the plane landed. I approached the bus that would take me to the city — less than a dollar for a 40-minute ride. At the door, the driver called out, “Заходите!” (“Come in!”). Worried he’d said “Уходите!” (“Go away!”), I scurried off to a safe distance. Then I approached again, gingerly, and slipped aboard.

On the bus, I stuffed my bomber jacket in my backpack. Still I sweated profusely as I chatted with Vlad on VKontakte and tried to keep my phone alive long enough to coordinate our meeting. The bus crossed the bridge where I’d first met Vlad in 2017, and pulled up to a crowded bus stop. I stumbled out with my bags and Vlad was waiting with open arms to give me a big welcome-to-Kaliningrad hug.

Vlad has his guests select a record to play from his collection. I chose Элла Фитцджеральд — Ella Fitzgerald.

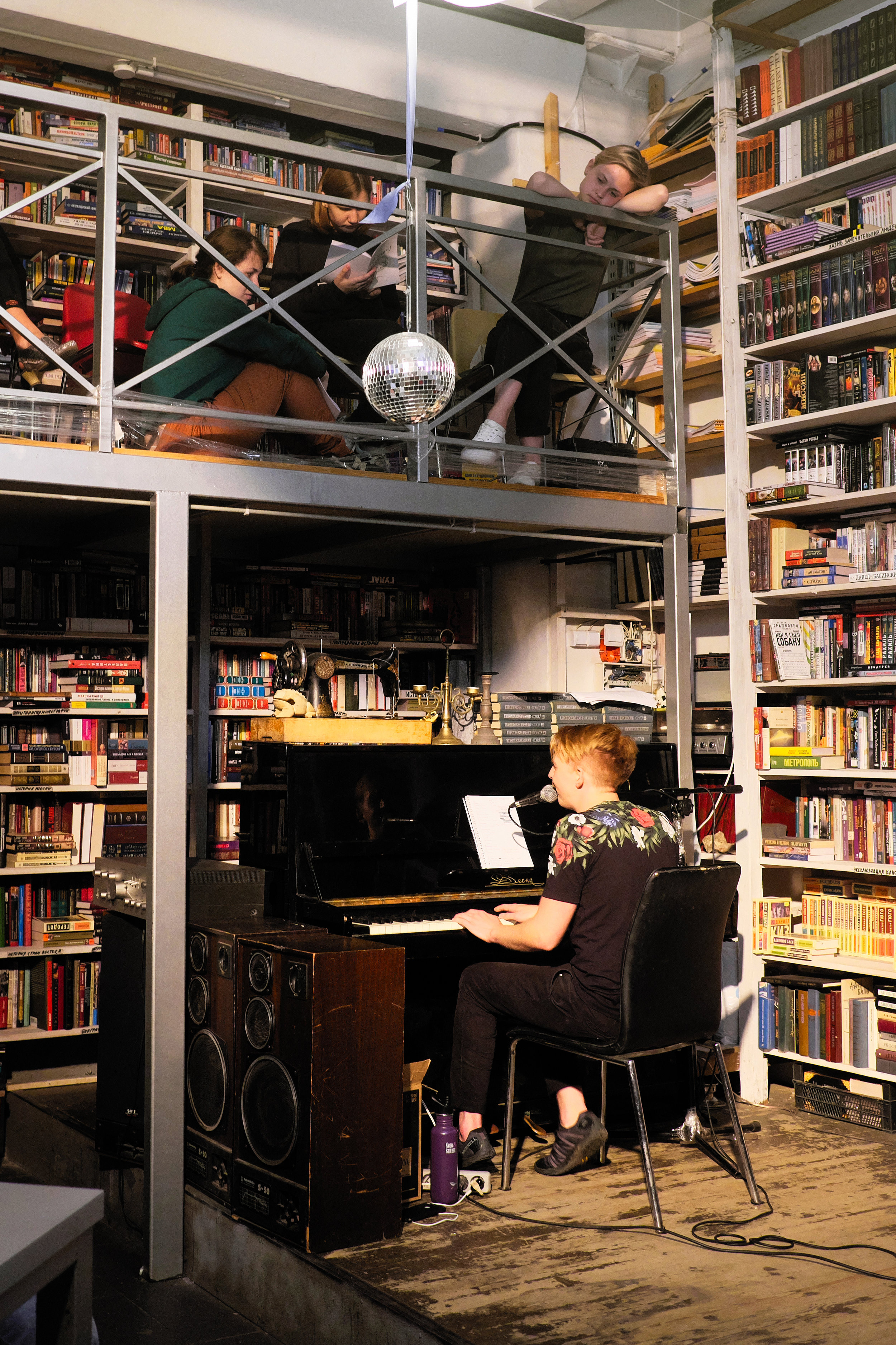

С милым рай и в шалаше — a Russian proverb meaning, “With one’s sweetheart, it’s paradise even in a hut.” Vlad and his basically-brother and sometimes-roommate Seryozha say this to one another, and while they don’t live in a hut per se, they do live in a humble seventh-floor walk-up art studio scattered with paintbrushes, canvases, and minimal amenities. Enormous windows fill the space with light and afford a wonderful view of the river and city.

I stored my luggage up in Vlad’s loft, then climbed back down the ladder with gifts.

In Russia, не принято идти к друзьями в гости с пустыми руками (it isn’t acceptable to go empty-handed to visit friends). I gave Vlad a small packet of granola from Portland along with a book called Speaking American. In our Skype conversations, we had read aloud from a dual-language book called Talking American. I noticed that Talking American was displayed on top of the piano, and Vlad added Speaking American to the arrangement.

(Side note: I cannot fathom the effort it must have taken to move that piano to this building’s seventh floor. I’m guessing it’ll be in that room as long as the building stands.)

Before my sweaty shirt had a chance to dry, Vlad proposed we take a trip to the Baltic Sea and stay the night there in a tent on the beach. I was tired, but I said yes, and soon we were in the car with Volodya and Anya, on our way to Zelenogradsk.

Once there, we went to Spar, a Russian grocery store, and I couldn’t stop smiling because it was all so different from what I’m used to — the products, the packaging, and above all the prices. From an American perspective, everything was dirt cheap.

View of the view from the boardwalk. Not sure why I didn’t try to get the actual sea in the picture.

We strolled along the boardwalk. It was after 10 PM and still not quite dark. I had gone to bed at 1 AM and woken up at 5, and it was starting to hit me. Still, Vlad had an all-important search for beer to complete. It’s illegal for stores to sell alcohol after 10 PM, but that wasn’t about to stop Vlad. The others and I sat on a bench and waited for him. Even at this hour the boardwalk was bustling, and to my amazement there were tons of families with young kids out. Evidently (P)Russians are more laid-back about bedtime than Americans.

In the distance, a long pier glowed with lights that slowly shifted from color to color — red to purple, purple to blue, blue to green. When Vlad returned, we went to the pier, and once there I realized that the lights were underneath, illuminating the water and nighttime swimmers below. Far down the pier, loud club music throbbed. A group of eight or more guys laughed and shouted, climbing onto the railing and jumping into the lit-up water below.

Finally it came time to set up the tents, near a series of quaint wooden swing sets. Vlad rummaged through his backpack and realized our tent was still in his apartment.

It was decided that Vlad and Volodya would find more alcohol while Anya and I set up the tent. Anya balked at this arrangement, not wanting to be left alone with someone who she couldn’t talk to, but Vlad reassured her that she could speak Russian with me. It did turn out to be a challenge at first, but an amusing one. I knew very little of the specialized vocabulary people might use to communicate as they set up a tent — words like “poles,” “stakes,” and “flysheet” — and inflate an air mattress — words like “valve” and “pump”.

It was a unique bonding experience.

Once we got through the more tricky parts of our job, Anya and I chatted more generally. Eventually we talked about how I’m a morning person, and I learned the Russian word for “lark” — жаворонок.

When Vlad and Volodya returned, they played a few songs on the guitar, and then the four of us — three owls and one lark — went to sleep in our single tent.

June 13, 2019

In the morning, everyone wanted to swim. I resisted, but ultimately gave in to saying yes to life. (I mentioned this and learned that Russians know about the Year of Yes.) I tiptoed into the sea, cringing each time the waves lapped a little higher on my body. The water was freezing cold. My friends asked me how this compared to the Oregon Coast, and I admitted that this water was actually a little warmer.

Find the Mediterranean Gull!

In the water, every hundred yards or so, a line of logs were placed vertically, separating the sea into segments. A dozen Black-headed Gulls perched on the logs nearest us, with one Mediterranean Gull mixed in. Lifer!

Vlad sang some lines from an eerie Doors song called “Bird of Prey,” then played it for me on his phone. I had never heard this song before. (Now it goes through my head all the time.)

We sang it as we packed up. Then we made our way along the boardwalk, where in the light of day I could now see intriguing features such as changing stations, hot corn booths, and a small shed with the word “ЛАЗЕРТАГ” (LASER TAG) on it. (See photo gallery above.)

On the drive back to Kaliningrad, we passed the most glorious fields of lupin. I could hardly believe my eyes. Lupin for days.

While Vlad was at work, I dealt with administrative tasks, practiced and prepared for my shows, and recorded a promo video for Vlad to post. I planned to go get groceries, but just as I got ready to leave, a huge thunderstorm broke out. Slumped so low in a chair that I was nearly horizontal, I must have hovered between sleep and awakeness for hours. Sometimes on tour you just have to accept that there will be weird days like this. Fortunately I hadn’t overbooked myself on this one, so it wasn’t a big deal to spend an afternoon decompressing.

Alex Popov, a friend I’d made on my first visit to Kaliningrad, invited me to the Upper Pond for a public outdoor rehearsal-performance by his friend Ilya Levashov’s band, for which Alex was playing percussion. On the way, we met up with Tatyana Decay, an edgy (in the sense of being avant-garde), artsy young woman whom Vlad had never met but knew from VKontakte. We hurried alongside the pond — which truly must be a lake — and after what felt like an epic quest but mostly amounted to continuing forward along a single path, we finally found the show.

This is an instrumental. I don’t think there’s any singing in this one.

Ilya describes Kellan as “Prussian post-folk,” and the songs are written in a revived Baltic Prussian language. They have a really fun, eclectic sound — here’s a little clip I took. You can also find their first EP, Ukpirms (“the very first” in Prussian), on Soundcloud. (While you’re at it, you can also check out Alex Popov’s neo-folk band, Sunset Wings.)

Good company.

After the performance, we walked to Ilya’s apartment, and eventually the kitchen was stuffed with seven people sitting and chatting, sipping tea and snacking. I marveled at Ilya’s hand-carved recorders, stored as if on display in a rack on the table, gleaming in warm shades of gold, chestnut, and burgundy.

June 14, 2019

Art.

A visit to the Amber Museum in the morning proved as colorful as Ilya’s recorders. I opted for the audio tour, and I have to confess that I retained absolutely nothing from it. Most interesting were the amber inclusions — bits of ancient life trapped and preserved in amber. I hunted around for ornithological inclusions and found exactly one, of a Gastornis feather. I also got this photo of an amber hornet on some amber cheese.

I was starving — not because of the amber cheese, though it certainly couldn’t have helped — so I hailed a Yandex Taxi. (Yandex Taxi is like the Russian Uber. They do also have Uber, but when you take it the drivers automatically know you’re not Russian.) At my destination, I paid the driver in cash, adding, “Сдачи не надо.” When he acted flabbergasted, I asked if I’d said it incorrectly. He told me I’d said it correctly — just no one ever says it.

Packets of tofu.

The vegan restaurant I’d been driven to, sadly, no longer existed. So I went to a tiny natural food store, Компас Здоровья (Health Compass), where I saw such wonders as seitan in jars, tofu in bags, and fancy nut/seed butters ranging from peanut to poppy seed. I bought vegan sausages and hot dogs, bread, vegan cheese, and a product claiming to be borsch crackers.

I squeezed in a bit of music practice, but before I knew it, I was again swept off to the Baltic Sea. It felt so contrary to my fundamental nature to take another leisurely trip like this. Left to my own devices, I work every single day, even in between show days on tours. At home, it takes a superhuman effort from Adam to get me to take a break.

I scrambled to pack some postcards so I could be productive at the sea.

Vlad and I took a bus with Tatyana Decay and another of Vlad’s friends, Axinya Makeeva. Once we reached Zelenogradsk (and made a pit stop at Spar), we set off in search of our campsite. I naively imagined we would camp in the same place we did the first night, but that one took just a few minutes to reach. This time was different. My feet began to ache from hiking on dry, unstable sand. Each step felt like several steps. What began as a lovely little seaside stroll turned into a grueling trek down a seemingly interminable beach.

I asked Vlad how much farther we had to walk. “I think… just five more minutes,” he told me.

Ten minutes later, I asked again, and he said, “Hmm. Maybe two more minutes.”

I couldn’t believe how tired I felt. We were probably walking for less than a half hour, but we were carrying camping gear, bags of food, and a big jug of water.

We watched for the green flash, but alas — no flash.

Finally, finally, we reached our destination, which to me looked no different from the mile of beach we had just passed over.

(I realize I probably sound disgruntled. Truthfully, these are happy memories.)

Vlad the Young Pioneer.

We set up camp. Vlad got a fire going. There was some dancing around to hits of the early 2000s, and then we roasted hot dogs over the fire. It was already dark, but after Axinya set up her tent, she went for the longest swim. Every few minutes I checked through binoculars to make sure she was still alive. When she finally came back, she claimed the water was warm, but I refused to believe it, having taken the plunge just a couple days before.

Shortly before midnight, I brushed my teeth and tucked myself into the tent, stuffing earplugs into my ears. Everyone else stayed up, but I needed something resembling a normal night’s sleep.

June 15, 2019

A few short hours later, the sun came up and I had no hope of sleeping any longer. I’m a lark through and through! I crept outside, trying not to disturb Vlad and Tatyana, and found myself in a small city of tents. Sometime after midnight, other friends of Vlad’s had apparently arrived.

Seryozha sat next to the fire — somehow still burning — looking cheerful as always but a little haggard. He explained that he had burnt his hand in the fire during the night and couldn’t sleep because of the pain. He was keeping the injured hand buried in the sand to try to soothe it.

I asked if he had taken any painkillers, and to my horror, he hadn’t. I tore into my backpack, found my first aid kit, and gave him some Ibuprofen. Unfortunately I didn’t have any burn ointment with me.

He took the Ibuprofen, and we chatted for a while. Eventually the pain lessened enough for him to attempt sleep. He lay down in a tent, leaving the opening unzipped so he hand could stay outside in the sand.

Greater Whitethroat (Серая славка)

Left alone, I climbed up a dune and a patch of trees and shrubs I hoped might be birdy. It wasn’t particularly active, but I did find my first Greater Whitethroat there — though I didn’t actually ID the bird properly till a couple days later. A flock of Mute Swans flew overhead, their wings whistling, and I went back to the campsite to scan the sea. Great Cormorants glided low over the water from time to time, but all was mostly quiet.

White Wagtail on the shores of the Baltic Sea

I sat in the shade of a tent and wrote postcards. My little friend that morning was a White Wagtail who paced urgently around the beach, tail bobbing up and down, tossing sand left and right with their beak.

Someone I didn’t know came out of Seryozha’s tent and introduced himself as Yury. For some reason — maybe the name — I responded in Japanese. Yury went for a brief swim, then back into his tent to sleep.

The morning went on like this, with people emerging sleepily to pee or swim (or possibly both), then returning to their tents. I sat there, somewhat mystified by it all. I felt like I had been dropped into some kind of absurdist play or silent film. The Lark and the Owls.

Вампир.

The tent housing Seryozha and Yury turned out to have another occupant, a young woman named Nastya Rychkova. Another tent held Volodya and Anya, who packed up and left while nearly everyone was napping.

It was still early in the day, but little by little more people began passing by. Some of them laid out towels or chairs and unfurled giant umbrellas. By 10 o’clock it looked like all those pictures of crowded beaches. This isn’t a sight we ever see in Oregon. What umbrella could withstand the wind?

I took out my own collapsible umbrella and hid under it. I had sunscreen, but since I was categorically opposed to swimming in the freezing water, I figured I might as well save it. Tatyana came outside and sat down next to me, and since she’s even paler than I am, I shared my small patch of shade with her.

I often find it hard to relax and just have fun. Sometimes a lack of clarity creates a barrier for me. In this case, I wasn’t sure how long we planned to stay at the sea. The other day we had gone home almost right away, so today I didn’t want to get too comfortable and then suddenly find out it was time to go. I considered asking Vlad how long we were planning to stay, but he was lying face down on a beach towel, dead to the world. Someone placed some smooth stones on his back, and every once in a while we’d add another one. He’d stir slightly and continue snoozing. (Later, when we were leaving, I noticed that Vlad had a sunburn on his back, with unburnt patches wherever the stones had been.)

Axinya struggles to make it back to her tent.

I finally loosened up when everyone (except Vlad, who was sleeping) started playing a game of Pictionary in the sand. I guessed a couple works of Russian literature correctly, and managed to get someone to figure out Anna Akhmatova’s Requiem.

After hours of everyone but me swimming on and off, someone finally explained to me that the water was indeed much warmer than the other day. Apparently those thunderstorms had something to do with it: the cloud cover had incubated the sea, raising the temperature.

Setting my doubts aside, I slathered my entire body with sunscreen. Then I wove through the people lounging and playing, and the kids whose job it was to pace around yelling “Горячая кукуруза! Горячая кукуруза!” (“Hot corn! Hot corn!”), and marched bravely into the water.

Packing up, or trying to.

It was perfect.

I suppose I can’t be too hard on myself for being so skeptical. What experience do I have with enormous bodies of water undergoing drastic temperature changes overnight?

“This is happiness,” Vlad said deliriously.

In the early afternoon, we packed up all the tents and trekked back into town, passing picturesque banyas and seaside villas. Vlad seemed a little woozy, and I suspected he was dehydrated. Before boarding our train, we hung around a little square by a market. Most everyone had ice cream, and I tried my first kvas (a fermented beverage made from rye bread), which was pretty tasty and refreshing.

On the train, we ended up sitting next to this sandy, surly-seeming shirtless jock. Yury wanted to play some songs, and asked the jock if he minded. The jock shrugged and continued scrolling through his phone and looking frowny.

Lest we forget.

Yury took out his guitar, which suddenly seemed gigantic. As Yury played and sang, I noticed the guitar pressing into the jock’s arm occasionally, and I wondered how pissed this guy — and everyone else — must be. In the US, I don’t think people are generally supportive of music on public transit.

I looked around nervously and was surprised and relieved to see other passengers smiling and nodding appreciatively. But the biggest surprise came during Yury’s next song, when the jock started mouthing the lyrics.

Music has charms to soothe a savage breast.

June 16, 2019

I woke up feeling grateful for a full night of sleep. The previous night, Vlad had gone to bed right away and Seryozha and I followed after watching the first part of The Little Golden Calf.

Today would be busy in the ways that come more naturally to me: a little show in the morning, a big show in the evening, and last-minute preparations in between.

Vlad and I hopped on a bus and when we got off, we ran into Yury and Nastya. I thought this was a coincidence, but it turned out I just knew nothing about what was going on. I met Olga, who had arranged this show for us, and we boarded a small bus — like an activity bus — bound for Polessk. I wished I’d brought a book — it turned out to be an hour drive. (I generally have a rule of always bringing a book with me, but sometimes I break it when I feel like I already have a million things with me. This tour taught me more than once that it’s always worth making room for that million-and-first thing, as long as that thing is a book.)

Still, the scenery deserved my attention. And one point when I was distracted by my phone, Vlad told me to look out the window, and waddling alongside the road was a White Stork. After this, I kept my eyes glued to everything passing by.

Walking through Polessk. Note Yury’s cool shirt.

Photo by Olga Popova.

In Polessk (population: 7000, though it seemed almost deserted), we played a concert at a “psychoneurological institution” — basically a residential care facility for adults with various disabilities. (First we stopped at a little grocery store with a dog at the door. See photos.) At the facility, Vlad, Yury, and I took turns playing songs for an enthusiastic audience, and Nastya contributed percussion with tambourine-esque bracelets. Afterwards, everyone wanted to talk to us and take pictures together, which was so sweet and fun. A large group of residents followed us all the way to the gates, waving and calling out farewells as we headed back through town to the bus stop.

Just as we turned the corner, I noticed two birds on a telephone wire. Common Redstarts! A new species for the life list. (No photos, though.)

In the town of Polessk are the ruins of Labiau Castle — Замок Лабиау. We wandered through a desolate courtyard, empty except for a headless statue and a sign that said Центр развития человека — Center for Human Evolution — which everyone thought was funny.

That evening, I played my show at Katarsis. I scarcely dared to hope for it to be as heartwarming as my 2017 show at the same venue. But I needn’t have worried — it proved to be one of the greatest experiences of my career. It’s difficult to identify what sets a show like this apart from others. The audience listened and applauded, as most audiences do. But they seemed more willing to engage, to participate. There was an electric, tangible connection between audience and performer. Moreover (and perhaps somehow a by-product of this connection), it felt like all judgment was suspended — like any imperfections in my performance were either irrelevant or added to the uniqueness of this particular show.

Does the distance an artist has traveled somehow heighten people’s sense of urgency to tune in and be present? Or is it the infrequency of performances that adds value? Many artists I know strive to play as many nights of the week as possible. Scarcity, though, could be more powerful than ubiquity.

Huge, huge thanks to Felix Morozov, who took photos and videos of the event!

Video by Felix Morozov. Cover of Весеннее танго (Spring Tango) by Valeriy Milyaev (Валерий Миляев).

Video by Felix Morozov.

Video by Felix Morozov.

Video by Vlad Barabashov.

After the show, so many people lined up to talk about the music and buy CDs and shirts. It brought me so much happiness to spend time with each person: the person whose child drew a picture of me during the show; the person who was so curious about my song Вертишейка (“Wryneck”); the person who especially loved “Overwintered”; the people who wanted to take pictures together. Among the photos that ended up in my possession were those taken with the fantastically mustached Vadim, spritelike Alesya, and super hip Nadya and Nastya (Smirnova, not Rychkova).

When I woke up, there was a tent in the living room.

Back at Vlad’s, a group of us hung out, eating and talking and listening to music. As I fell asleep — before everyone else, of course — I felt overcome by a bittersweet gratitude for this night, this place, and these friends I’d soon have to leave behind.

June 17, 2019

My last full day in Kaliningrad involved an adventure with two almost-total strangers, Nadya and Nastya (Smirnova, not Rychkova). After a quick breakfast, we set out on foot, walking along the Pregolya River. Across the water, there was Kneiphof — Kant Island — and the spire of Königsberg Cathedral.

Hooded Crow. The dome beyond the trees belongs to the historic Jewish orphanage building.

Nadya and Nastya had offered the previous night to accompany me on an excursion to the Curonian Spit — Куршская коса. The Curonian Spit is a narrow, 60-mile long stretch of land — or sand — that separates the Curonian Lagoon from the Baltic Sea. It spans from Kaliningrad to Lithuania, and it’s a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

When we got to the bus, the tour guide struggled to find my un-Russian last name on her roster. Finally she located it and waved me aboard, then as an afterthought exclaimed at my name’s strangeness and asked if I was German or what. I was already moving down the aisle of the bus, my back to her, so I just pretended I either didn’t hear or didn’t understand.

We sat in the very back, like mischievous teenagers. Over the tinny intercom, the guide talked on and on about the Curonian Spit and amber. I tried to follow the lecture at first, but quickly became exhausted and let the words blur together. She passed around maps and other visual materials. One of the handouts depicted something that made the three of us grimace, but I have no recollection of what it was.

Our first stop was at Биологическая станция Рыбачий — Rybachy Biological Station, a bird banding station. Senior researcher Anatoly Shapoval led us down a trail into the forest, telling the group about the station. I was the only person with binoculars. We stopped in a clearing where interpretive signs detailed the birds of the area. The English translations made me chuckle — “Rear Birds” instead of “Rare Birds,” “Eruption” instead of “Irruption”. For the bird Сизоворонка (European Roller), the English account was headed with the German “Blauracke”.

I stayed at the edges of the group, watching the Barn Swallows darting around overhead, and a Common Redstart singing from a branch halfway up a pine.

We emerged from the forest and into an open area, then followed Anatoly into a vast system of nets within nets within nets. Inside, a Yellowhammer — Обыкновенная овсянка — fluttered fruitlessly against the soft walls.

One of the innermost nets contained butterflies. While Anatoly talked about butterflies, I stood shielding my face from the glaring sun. A woman in a white linen bucket hat asked me if I needed a hat. It sounded like an offer and not like a general inquiry, so I hurried to reassure her.

Anatoly then led us back into the woods, to a sort of cabin with an open window, like a store at a summer camp. This was the Fringilla Field Station. From the window, Anatoly gave a complete bird banding demonstration. First he showed us the many different band sizes, offering examples of birds that would require each size. Then he retrieved a small bag, from which he produced a tiny songbird.

I started filming at this point, so you can watch it all, following this play-by-play in English: Holding the bird in his hand, Anatoly casually shuffles through some papers. A concerned member of the group asks if this process causes the bird stress, and he says, “Don’t worry. All their lives, birds live under the influence of stress. Without stress, they simply can’t live.” Then, adjusting his grip, he presents the bird as if they are a carnation. He explains that the species isn’t one most people will know the name of, and identifies the bird as a Серая славка — Greater Whitethroat, or Sylvia communis in Latin. Still holding the bird, he begins writing in his log, examining the bird’s eye color and plumage to determine that this is a female. He says that there isn’t a way to tell whether this is a juvenile or an adult, because they have the same plumage. He takes a measurement. Then he explains the importance of fat to a migratory bird who will fly 7800km (4846 miles) to winter in Sudan, Ethiopia, etc. He blows on the bird’s chest to find out how much fat this bird has on her, and writes down “мало” (not much), noting to us that she still has till the end of August (remember, this was June 17th). Last, he explains that it is difficult to weigh a bird without letting them fly away. The solution, we see, is to plop the bird facedown in a cone. Finally, after he records her weight, he warns the “paparazzi” to be prepared, and releases the bird, to everyone’s delight.

Our excursion then took us further along the Curonian Spit, bringing us to the Dancing Forest — Танцующий лес — where the trees twist in spooooky, mysteeerious ways. (It’s very beautiful, really.)

Who gave you permission to dance like that, forest?

While we were there, our guide came up behind us and asked Nastya and Nadya very insistently where their comrade (me) was from, and I couldn’t help but laugh. We told her, and as she walked away she mused again on how she had wondered where on earth my last name could have come from.

Nadya poses, Nastya shoots.

Our last stop was Efa’s Height — Высота Эфа. A boardwalk led us through the trees and gradually upward. Common Chaffinches — Зяблики — serenaded us as we hiked. (Another bird on the life list!) At the height of the Height, a platform gave us views of the Curonian Spit, with the lagoon on one side and the sea on the other. We shared a moment of doubt over which side was the lagoon and which side was the sea. Most importantly, Nastya and Nadya created some glamorous Instagram content.

Photo by Nadya Yarkovich.

Domovoy and compass.

Before we left this stop, I searched the shop stalls by the entrance for a Christmas ornament. Last Christmas, I went through boxes of old ornaments and determined that almost none of them held any significance to me. I hung up a European Robin ornament from Stonehenge and a caterpillar mascot keychain from the Edo-Tokyo Open Air Architectural Museum, and decided to start a new tradition of collecting souvenir ornaments on my tours and other travels. I often admire but pass over cute little trinkets in gift shops, not wanting to clutter up the house with useless stuff. Usually I opt for useful items, or nothing at all. This new tradition would give me an excuse to buy small, inexpensive, purely decorative items. They could occupy space that would have been set aside anyway for Christmas ornaments, and the joy and happy memories they bring me wouldn’t be diluted by blending into the background of everyday life.

White Wagtail in the cemetery.

I found a cute ornamental Домовой — Domovoy, a Slavic household god. When your cat seems to be staring at something invisible, people say they’re looking at the Domovoy. Nadya and Nastya very sweetly bought this ornament for me, as well as a Kaliningrad keychain with a compass — to help me return, they said. ❤️

We returned to Kaliningrad, wandered through an old cemetery, and walked Nastya to her place. Then Nadya and I went to Evropa, a mall, which was exactly like every mall in the world. I wanted to go to some Polish clothing stores. I had really liked Yury’s T-shirts, and when I asked him where he got them he said “a Polish store at Evropa”. I didn’t find any shirts like Yury’s, but I did end up getting a different one. (A month and a half later, I saw a tween wearing the same shirt in Vancouver, BC.)

Eventually, Nastya met us at a Korean restaurant, and afterwards we were reunited with Vlad and Seryozha. Nadya found me a vegan-friendly popsicle that — to my shock while eating it — ended up containing Pop Rocks. Together, the five of us walked to Felix Morozov’s place.

All I knew was that we were visiting Felix, so it was a surprise to me when it turned out to be a tea ceremony. We gathered around a tray on his floor and he passed around some loose tea for each of us to smell. Then (and I don’t remember the exact order of these steps) he splashed hot water in all our little cups, rinsing them out. He steeped the tea. He poured the tea into the little cups with a certain sprezzatura, alternating between all six cups in one continuous pour. After we sipped this tea, he passed around other teas and had different people choose. Again Felix rinsed and steeped and poured. It was all very intimate and elegant. On his computer, selected with me in mind, birdsong played.

At some point Felix handed me a tea to smell, which I did. “Запах,” I murmured as an assessment, even though this just means “smell”. For the next twenty minutes (if not longer) we laughed about this and came up with many examples of circumstances where a person might simply say “запах” and avoid disclosing whether they found it good or bad.

It was the perfect way to spend my last evening in Kaliningrad.

Felix, Nadya, Seryozha, me, Vlad, Nastya.

Photo by Felix Morozov.

As we left, I expressed my gratitude, and my sadness to be leaving. Knowing the word “грустно” (“sad) but forgetting its noun form грусть (“sadness”), I said “грустность”. (Not an unreasonable way to turn something into a noun in Russian.) “Грустности нет,” Felix kindly informed me. (“There is no ‘sadness’” — meaning this word for ‘sadness’.) But it had also been amusing, like something a child would say. “Грустности нет!” I wailed, pretending to cry.

June 18, 2019

After packing my suitcase, I bestowed Harlequins T-shirts upon Seryozha and Vlad. They had done so much for me, and I wanted them both to have something to remember me by.

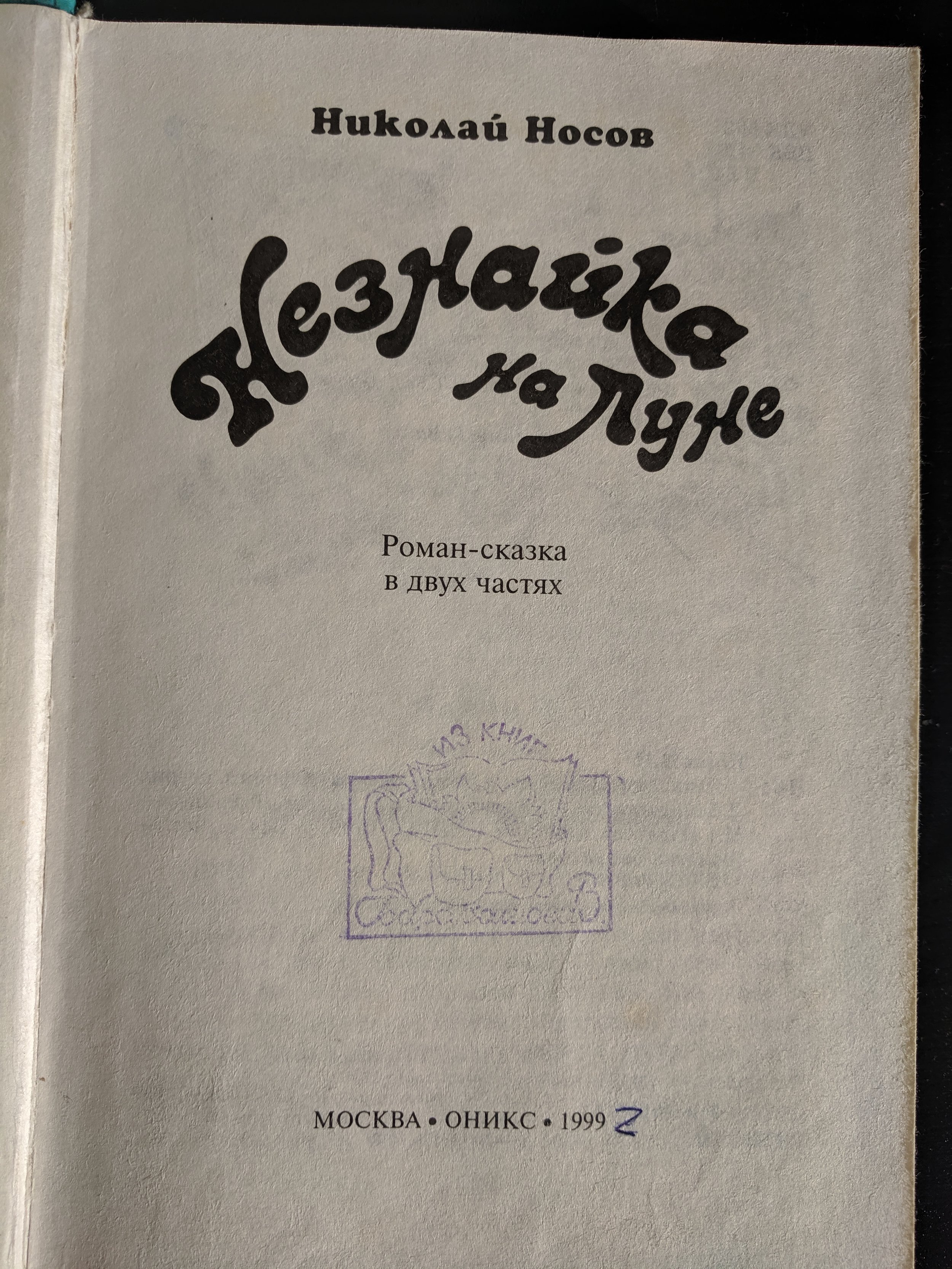

Vlad, in turn, searched his bookshelf and gave me an incredibly precious gift: a copy of one of his favorite books from childhood, Незнайка на луне (Dunno on the Moon — Dunno being the story’s know-nothing anti-hero). Inside the cover, a stamp identified the book as being “из книг Барабашова В.” (“from the library of Barabashov V.”). I hardly knew how to respond, except to hug him.

Seryozha, for his part, sent me off with a moving dance performance.

Vlad walked me down the seven flights of stairs to the alley where my taxi was waiting. After a long hug, we said our goodbyes. On the drive to the airport, I fixated on the city passing by, trying to eke more memories out of Kaliningrad. In the airport, I lingered in a gift shop for as long as I could before going through customs and security. And on the plane, I contemplated my calendar on my phone, already plotting my return.